Monday, August 30, 2010

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Occultural Studies 1.0 -- Eugene Thacker on Hideous Gnosis at Mute Magazine

(reposted from Mute Magazine)

Occultural Studies 1.0: Black Meta

Increasingly DIY and nihilistic, it's not surprising that contemporary philosophy is drawn to the untilled fields of undead subculture. Recent book, Hideous Gnosis, unleashes a bloodthirsty plague of para-academic commentary upon Black Metal, but, asks contributor Eugene Thacker, ‘how to talk about a music that refuses to be talked about?’

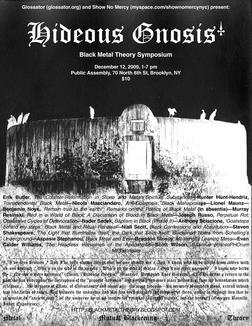

The book Hideous Gnosis: Black Metal Theory Symposium is based on a symposium held in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in December of 2009. Now, for many, the idea of an academic symposium dedicated to black metal is about as ridiculous as a black metal band with songs like ‘The Subculture of the Tritone Chord and its Posthuman Discontents’ or ‘The Hegemony of Your Biopolitical Jouissance.’ Certainly those familiar with the various mutations of cultural studies – particularly in the US – will not be surprised to find academics talking about culture and music. But that metal, that most anti-intellectual of all musics, could be the topic of intellectual inquiry would seem to be the height of absurdity. Either these guys take themselves way too seriously, or they’re so self-aware of being ‘meta’ that they end up enjoying themselves just a little less. One imagines professors giving the ‘horns’ sign during a lecture for emphasis (definitively replacing the more tentative ‘bunny quotes’ gesture). At the very least one would hope to find all speakers donning corpse paint or monkish, hooded robes. Whatever the case, the event caught the attention of the New York Times, which ran an article on it immediately.i A short time after the symposium, the talks – along with additional essays – were collected together in book form as Hideous Gnosis (a second symposium, entitled ‘Melancology’, is planned for January 2011 and will be held in a London anatomy theatre).

Image: Hideous Gnosis book

I’m being a little droll here because I myself am one of the contributors to the Hideous Gnosis book. Whether one comes to it from philosophy, cultural studies, political theory, or some other field, cultural commentary always places one in a tenuous position. As a scholar and academic one treats the material one is commenting on with a certain degree of seriousness and rigour; but as a fan (or consumer…) one is also aware that, at the end of the day, it’s all a big joke. So I begin this review with the following: ‘black metal theory’ not only challenges what is or isn’t black metal, but it also challenges what cultural commentary is, and the claims it makes.

The symposium and Hideous Gnosis book is the brainchild of Nicola Masciandaro, who teaches at Brooklyn College and is trained in medieval literary studies. Hideous Gnosis is a strange kind of book – it’s not exactly an academic anthology, in that the texts range from poetic evocations of black voids, to black metal manifestos, to band interviews, to historical essays and scholastic commentary. It’s also not quite music journalism, in that many of the texts are quite demanding, freely dropping quotes from Carl Schmitt, Arthur Schopenhauer or Michel Foucault instead of album reviews or the requisite history of the genre.

In music writing of this type, one typically finds a focus on one of four things: musical form, lyrical content, subculture and aesthetics, or politics and ideology. Each contribution to the volume touches on all of these to varying degrees, but what really distinguishes the writing in Hideous Gnosis is that each contribution revolves around a fundamental contradiction: how to talk about a music that refuses to be talked about? Or better: how to think about a music that negates all thought (in so far as ‘thought’ denotes order, system, and the production of knowledge – by human beings, for human beings)? As Masciandaro has noted in an interview, ‘there’s lots of resentment toward a sensible discourse around black metal… . Its center of gravity is an essential negativity…’ii

Image: Poster for Hideous Gnosis - Black Metal Theory Symposium

This central antagonism runs through nearly all the writing in Hideous Gnosis. That no one can agree on what is or is not black metal is not surprising – every music genre is defined by such debates. What’s more interesting is that in Hideous Gnosis, each attempt to think about black metal also puts itself forth as an antagonism, as a negation – an anti-natural nature, an anti-political politics, and an anti-philosophical philosophy.

Some of the authors think about black metal in terms of nature – but a concept of nature quite different from the romantic-hippie view of a nature beneficial for us (much less a nature we are ordained to save), as well as from the blood-and-soil view of nationalism. A casual look at black metal album covers and song lyrics reveals an ambivalent approach to nature, at once predatory and decaying, undergoing a constant metamorphosis that produces nothing. This is reflected in much of the writing: Steven Shakespeare’s more poetic text evokes pantheism, Schelling, and the idea of ‘absolute sound’; Aspasia Stephanou traces the motif of the wolf, lycanthropy and the forest in black metal; and Anthony Sciscione comments on its themes of cold and fire.

Other authors think of black metal in terms of politics – but a politics that attempts to avoid the poles of right and left, nationalism or ecology. Scott Wilson discusses the concept of sovereignty in the history of political thought, contrasting the archetype of the warrior to the soldier in black metal; Joseph Russo points out the central role that the body plays in black metal, albeit an ambivalent body of decay and rot; and in a sort of tête-à-tête the essays by Benjamin Noys and Evan Calder Williams approach black metal from different viewpoints – Noys questions both the left-wing and right-wing tendencies of black metal (both retaining a fidelity to Carl Schmitt’s maxim ‘remain true to the earth’), while Williams sees black metal as raising the stakes on what politics can mean, imagining a body politic without a head, a ‘war by the human in the name of the inhuman.’iii Whereas for Williams, black metal’s antagonism is really about the ‘war of totality against itself’, for Noys the best black metal can manage is the kind of self-reflexive ‘meta-fascism’ one can also find in punk and industrial music.

In addition to nature and politics, still others in the Hideous Gnosis volume think of black metal in terms of philosophy – or mysticism – because in black metal they increasingly become one and the same. Erik Butler examines black metal in relation to early modern monastic traditions; Hunter Hunt-Hendrix provides a manifesto for ‘transcendental black metal’; Masciandaro utilises the medieval catena or ‘chain’ form of writing to comment on the relation between black metal and cosmos (order); Niall Scott provides some ruminations on black metal as a form of religious confession; and my own contribution borrows the Scholastic quaestione to trace the role of demons and demonology vis-à-vis black metal.

Whether Hideous Gnosis definitively answers questions about nature, politics, or religion is beside the point. Nearly all the contributors agree that there is something here worth thinking about, though what that is differs a great deal from one text to another. Strangely, while I imagine the Hideous Gnosis contributors are also fans of the music, almost no one defends black metal, at least not to the hilt. And, in a way, black metal is indefensible – which makes it both appealing and frustrating for the philosopher.

Image: Poster for Melancology - Black Metal symposium part II

Music and language exist in an antagonistic relation to one another. The most verbose and baroque of writers often trip up when writing about music and its effects – for instance, while music was central to Schopenhauer’s philosophy, in The World as Will and Representation he only manages to scribble down a few paragraphs, and even those are riddled with vague comments about music as some kind of inhuman, cosmic ‘Will’. At the same time, music bears a close relationship to poetry, with its emphasis on meter, cadence and rhyme. Many a classical composer has set pieces to poems – indeed western classical music, from the liturgical texts of Christian masses to modern opera, is so closely tied to language that it is nearly impossible to separate them. This back-and-forth is perhaps best symbolised by John Cage’s anthology of writings, scores and performance texts enigmatically entitled Silence.

If there is an antagonism between music and language, things get even more messy when we consider language about music. There’s something superfluous about music criticism, let alone something so grotesque as a philosophy of music. As with any specialised field, everyone has their opinion, debates ebb and flow, and the alibi of subjective aesthetic experience serves to keep the discussion or debate alive.

All of this is fine. But it is when we come up against a music that is so saturated with antagonism – both internally and in its relation to the world – that we see how these antagonisms endemic to music become apparent. I would argue that black metal is an example of such a music. There is a certain impasse in black metal, an abyss at its core that is, in a way, what black metal is. My own take – and many may disagree with this – is that the abyss at the core of black metal shares many affinities with negative theology, and what scholars often refer to as ‘darkness mysticism’.iv I would even argue that to understand black metal beyond a music genre, a marketing category, or a subcultural style, and to understand it aesthetically and politically, one has to read Dionysius the Areopagite or John of the Cross. This is the musical equivalent of negative theology – without god. One of my favorite quotes from Hideous Gnosis comes from Erik Butler, who reminds us of why metal is heavy:

The heaviest metal found on Earth is uranium: enriched uranium is plutonium, a substance that conjures up the Lord of the Dead. Heavier elements occur only in space, where Pluto mournfully orbits the Sun at a distance of 3,666 million miles. Somewhere still farther off in the void floats the philosopher’s stone, black metal.v

We live in a time of levitation; everything from the information we process to the bodies we wear is portrayed as weightless, mutable, and subject to infinite, personalised variation. At the same time, we are constantly reminded of just how leaden and earth-bound we are, from the thick, viscous oil that seeps onto the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, to the sheer biomass of waste produced by the world’s major cities. Perhaps this is why metal is heavy – not because it is about nature, politics, or religion, but because it gets at a central ambivalence surrounding material culture.

I’m also reminded of Blake’s famous line about the ‘dark Satanic Mills’ of industrial London – perhaps mills similar to the steel factories outside the schoolhouse in Aston, where a young Tony Iommi listened to their incessant, inhuman churning.

Eugene Thacker is a New York based writer and the author of Horror of Philosophy (forthcoming from Zero Books). He teaches at The New School and is a scholar-in-residence at the Miskatonic University Colloquy for Inexistent Cryptobiology

INFO

Nicola Masciandaro (ed.), Hideous Gnosis: Black Metal Theory Symposium, New York: Createspace, 2010.

FOOTNOTES

i The article is online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/15/arts/music/15metal.html?_r=1.

ii Ibid.

iii Hideous Gnosis, p. 136.

iv On darkness mysticism see Denys Turner, The Darkness of God, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

v Ibid., p. 30.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)